Too much, for example, the contributions of black sociologists and intellectuals who have influenced the development of the field are ignored and excluded from the standard narratives of the theory of sociology. In honor of the satisfy.

Sojourner Truth, 1797–1883

Anna Julia Cooper, 1858-1964

SPIDERWEB. DuBois, 1868-1963

Charles S. Johnson, 1893-1956

E. Franklin Frazier, 1894-1962

Oliver Cromwell Cox, 1901-1974

CLR James, 1901–1989

St. Clair Drake, 1911–1990

James Baldwin, 1924-1987

Frantz Fanon, 1925-1961

Audre Lorde, 1934–1992

Too often, the contributions of black sociologists and intellectuals who have influenced the development of the field are ignored and excluded from the standard narratives of the history of sociology. In honor of Black History Month, we highlight the contributions of 11 important people who have made valuable and lasting contributions to the camp.

Sojourner Truth, 1797–1883

Sojourner Truth was born into slavery in 1797 in New York as Isabella Baumfree. After her emancipation in 1827, she became an itinerant preacher under her new name, a noted abolitionist and advocate of women’s suffrage. The sign of truth about sociology was left when she gave a now famous speech in 1851 at a conference on women’s rights in Ohio. Entitled for the key question she pursued in this speech, “Am I not a woman?”, Transcription has a part of sociology and feminist studies. It is considered important for these fields because, in it, Truth laid the foundation for the theories of intersectionality that would follow much later. Her question emphasizes that she is not considered a woman due to her race. All ‘ era it was an identity reserved exclusively for those with white skin. Following this speech, she continued to work as an abolitionist and, later, a black rights advocate.

The truth died in 1883 in Battle Creek, Michigan, but his legacy lives on. In 2009, she became the first black woman to have a bust of her likeness installed in the US capital, and in 2014 she was placed on the Smithsonian Institution’s “100 Most Significant Americans” list.

Anna Julia Cooper, 1858-1964

Anna Julia Cooper was a writer, educator, and public speaker who lived from 1858 to 1964. Born into slavery in Raleigh, North Carolina, she was the fourth African American woman to earn a doctorate – a Ph.D. in history at the University of Paris-Sorbonne in 1924. Cooper is most important scholars in US history, as his work is a staple of early American sociology and is often taught in sociology, women’s studies and breed courses. His first and only published work, Una voce dal sud, is considered to be one of the earliest conceived black feminist joints in the United States. In this work, Cooper has focused on education for black girls and women as central to the advancement of blacks in the post-slavery era. It also critically addressed the realities of racism and economic inequality faced by blacks. Her collected works, including her book, essays, speeches and letters, are available in a volume entitled The Voice of Anna Julia Cooper .

Cooper’s work and contributions were commemorated with a United States postage stamp in 2009. Wake Forest University is home to the Anna Julia Cooper Center on Gender, Race, and Politics in the South, which focuses on advancing justice through scholarships intersectional. The Center is run by Dr. Melissa Harris-Perry, a political scientist and public intellectual.

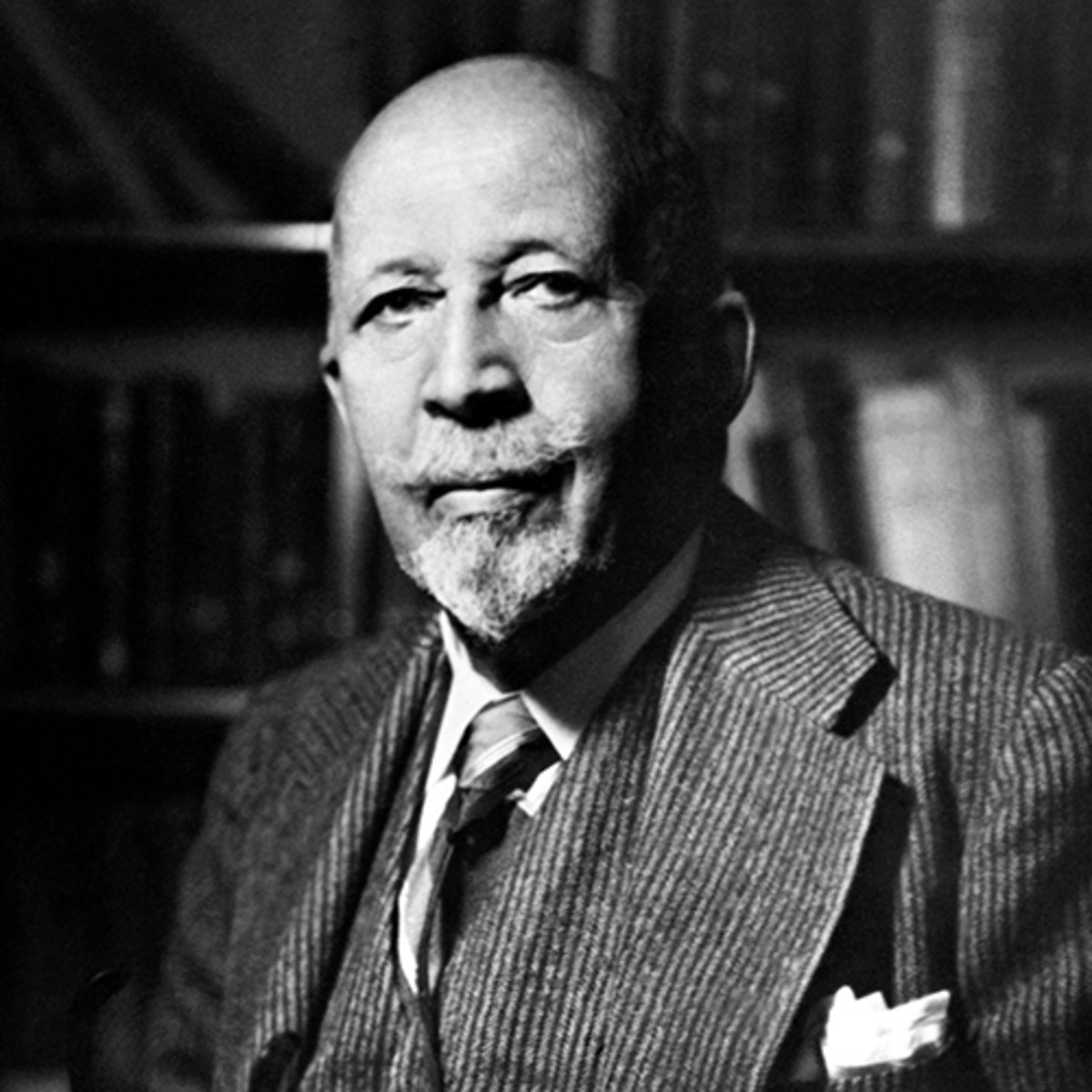

SPIDERWEB. DuBois, 1868-1963

SPIDERWEB. DuBois, along with Karl Marx, Émile Durkheim, Max Weber and Harriet Martineau, is considered one of the founding thinkers of modern sociology. Born in Massachusetts in 1868, DuBois would become the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University in sociology. He worked as a professor at Wilberforce University, as a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, and later as a professor at the University of Atlanta. He was NAACP founding member.

DuBois’s most important sociological contributions include:

The Philadelphia Negro (1896), an in-depth study of the life of African Americans based on in-person interviews and census data, which illustrated how social structure shapes the lives of individuals and communities.

The souls of the black people (1903), a treatise on what it means to be black in the United States and a demand for equal rights, in which DuBois endowed sociology with the profoundly important concept of “double consciousness”.

Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (1935), a richly researched historical account and sociological analysis of the role of race and racism in the division of workers in the Reconstruction South, who might otherwise have bonded as a common class. DuBois shows how the divisions between black and white southerners set the stage for the passing of Jim Crow’s laws and the creation of a black underclass without rights.

Later in his life, DuBois was investigated by the FBI on charges of socialism due to his work with the Peace Information Center and his opposition to the use of nuclear weapons. He later moved to Ghana in 1961, renounced his American citizenship and died there in 1963.

Today, DuBois’s work is taught in basic and advanced level sociology classes, and is still widely cited on contemporary scholarship. His life’s work served as the inspiration for the creation of Anime , a critical journal of black politics, culture and society. Each year the American Sociological Association awards an award for a career of distinguished scholarships in his honor.

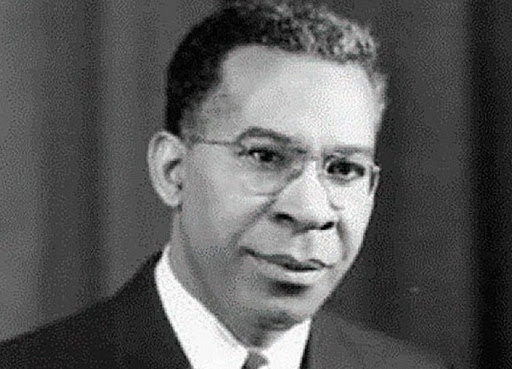

Charles S. Johnson, 1893-1956

Charles Spurgeon Johnson, 1893-1956, was an American sociologist and the first black president of Fisk University, a historically black college. Born in Virginia, he holds a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Chicago, where he studied among the sociologists of the Chicago School. While in Chicago he worked as a researcher for the Urban League and played a leading role in the study and discussion of race relations in the city, published as The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Riot and Race Relations. In his subsequent career, Johnson focused his scholarship on a critical study of how legal, economic and social forces work together to produce structural racial oppression. His notable works include The Negro in American Civilization (1930), Shadow of the Plantation (1934) and Growing Up in the Black Belt (1940), among others.

Today, Johnson is remembered as a leading early scholar of race and racism who helped establish a critical sociological focus on these forces and processes. Each year, the American Sociological Association awards an award to a sociologist whose work has made a significant contribution to the struggle for social justice and human rights for oppressed populations, named after Johnson, along with E. Franklin Frazier and Oliver Cromwell Cox. His life and work are described in a biography titled Charles S. Johnson: Leadership Beyond the time of the Age of Jim Crow.

E. Franklin Frazier, 1894-1962

E. Franklin Frazier was an American sociologist born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1894. He attended Howard University, then went on to graduate work at Clark University and eventually earned a PhD. in sociology from the University of Chicago, along with Charles S. Johnson and Oliver Cromwell Cox. Before arriving in Chicago he was forced to leave Atlanta, where he taught sociology at Morehouse College, after an angry white mob threatened him following the publication of his article, “The Pathology of Race Prejudice.” After his PhD he Join at Fisk University, then Howard University until his death in 1962.

Frazier is known for works including:

The Negro Family in the United States (1939), an examination of the social forces that shaped the development of black families from slavery onwards, which won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 1940.

Black Bourgeoisie (1957), who critically studied the subdued values adopted by middle-class blacks in the United States, among others.

Frazier contributed to the drafting of the postwar UNESCO declaration The Question of Race , a response to the role played by that race in the Holocaust.

Like WEB DuBois, Frazier was vilified as a traitor by the United States government for his work with the Council on African Affairs and his activism for black civil rights.

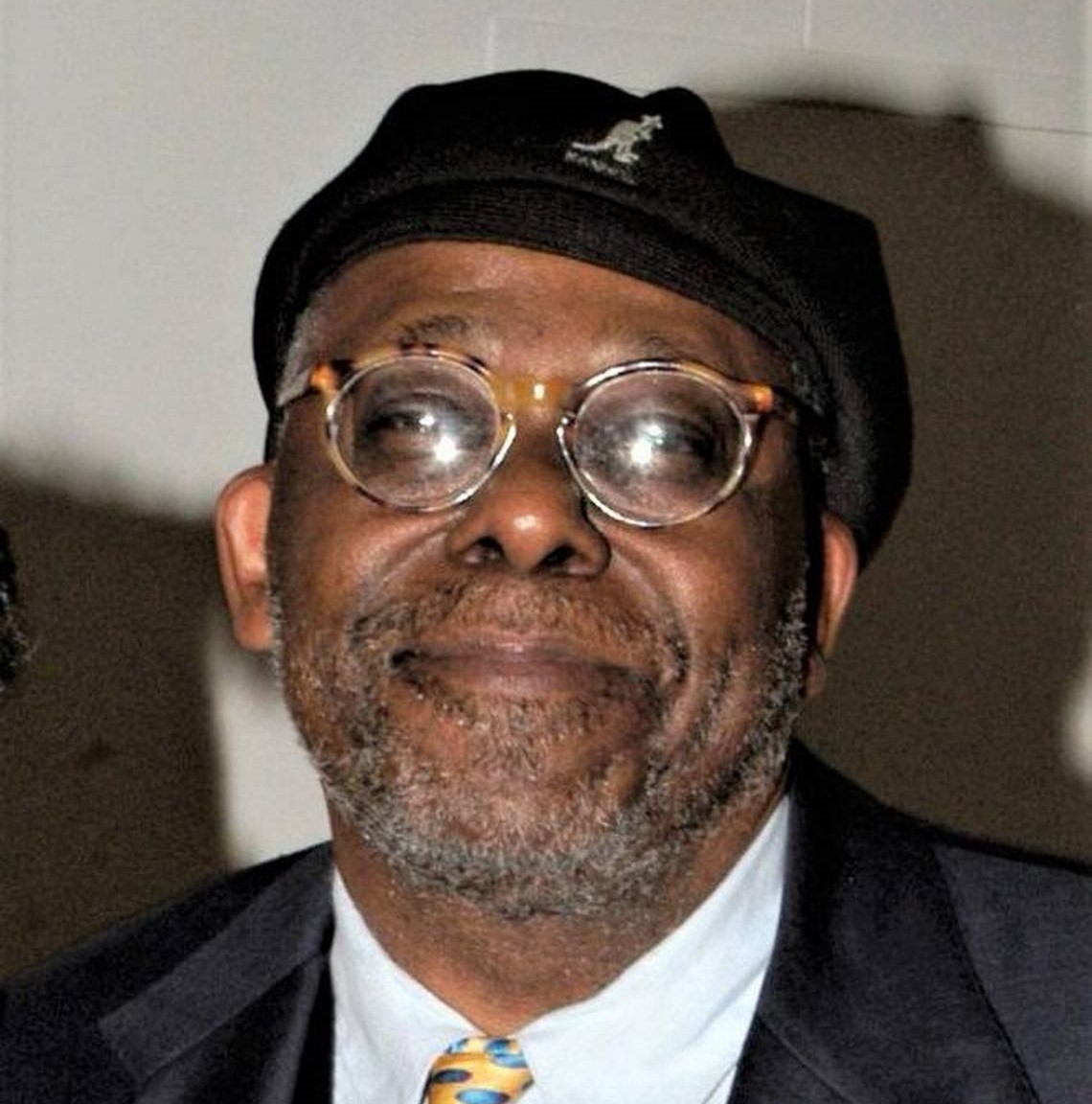

Oliver Cromwell Cox, 1901-1974

Oliver Cromwell Cox was born in the city of Trinidad and Tobago, Port-of-Spain in 1901 and emigrated to the United States in 1919. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Northwestern University before pursuing a masters degree in economics and a PhD. in sociology from the University of Chicago. Like Johnson and Frazier, Cox was also a part of the Chicago School of sociology. However, he and Frazier had very different views on racism and race relations. Inspired by Marxism, the hallmark of his thinking and work was the idea that racism developed within the system of capitalism, and is primarily motivated by the drive to economically exploit people of color. His most notable work is published in 1948 Caste, Class and Race. It contained important critiques of how both Robert Park (his teacher) and Gunnar Myrdal framed and analyzed race relations and racism. Cox’s contributions have been important in orienting sociology towards structural ways of seeing, studying and analyzing racism in the United States.

From the mid-century onwards he taught at Lincoln University in Missouri, and later at Wayne State University, until his death in 1974. Oliver C. Cox’s Mind offers a biography and in-depth discussion of Cox’s intellectual approach to race and to racism and its body of work.

CLR James, 1901–1989

Cyril Lionel Robert James was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1901 under British colonization in Tunapuna. James was a fierce and formidable critic and activist against colonialism and fascism. He was also a fierce advocate of socialism as a way out of the inequities built into government through capitalism and authoritarianism. He is well known among social scientists for his contributions to postcolonial scholarship and for writing on subordinate subjects.

James moved to England in 1932, where he devoted himself to Trotskyist politics, and launched an active career of socialist activism, writing pamphlets, essays and dramaturgy. She experienced a bit of a nomadic style during her adult life, spending time in Mexico with Trotsky, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in 1939; he then lived in the United States, England and his homeland of Trinidad and Tobago, before returning to England, where he lived until his death in 1989.

James’s contributions to social theory come from his non-fiction works, The Black Jacobins (1938), a history of the Haitian revolution, which was a successful overthrow of the French colonial dictatorship by slave blacks (the most successful uprising of its kind in history); and Notes on the dialectic: Hegel, Marx and Lenin (1948). His collected work and interviews are featured on a website titled The CLR James Legacy Project.

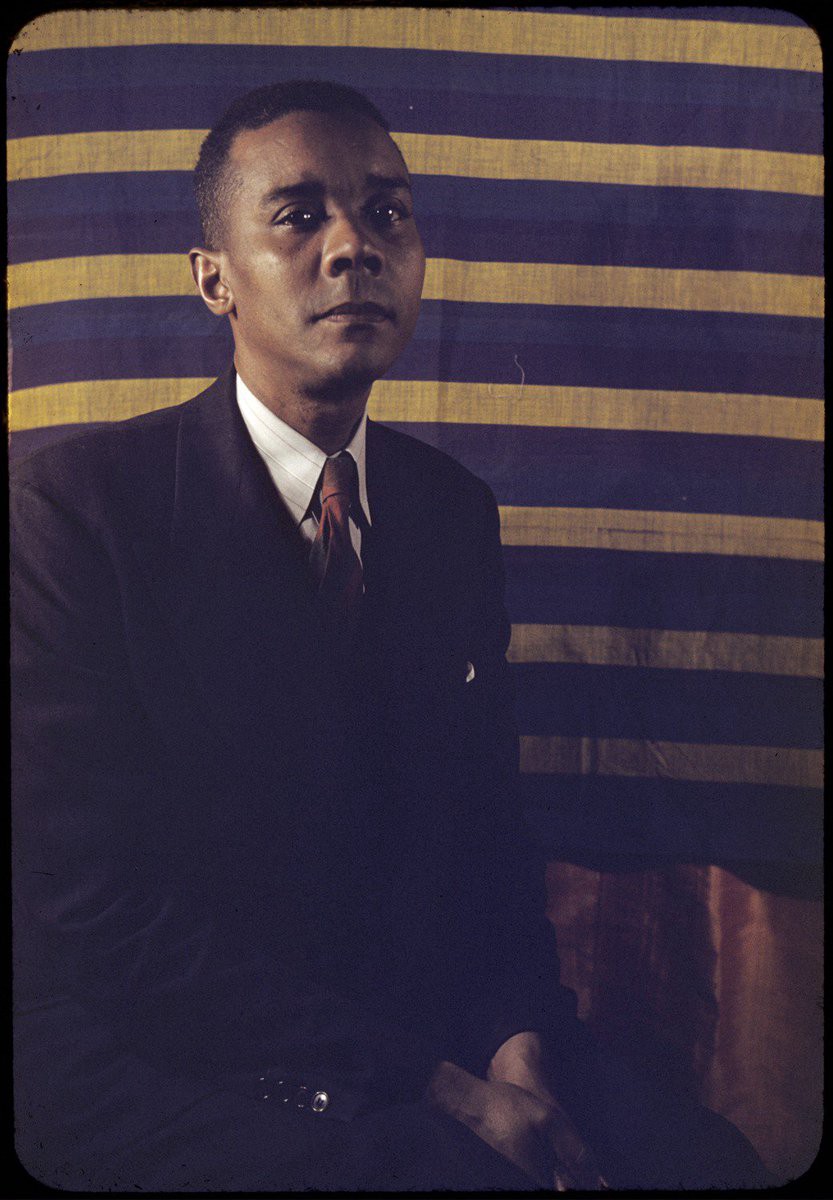

St. Clair Drake, 1911–1990

John Gibbs St. Clair Drake, known simply as St. Clair Drake, was an American urban sociologist and anthropologist whose scholarship and activism focused on mid-20th century racism and racial tensions. Born in Virginia in 1911, he start studied biology at the Hampton Institute, then completed a Ph.D. in anthropology at the University of Chicago. Drake then became one of the first black professors at Roosevelt University. After working there for 23 years, he leave to found the African and African American Studies program at Stanford University.

Drake was a black civil rights activist and helped establish other black curricula nationwide. He was active as a member and advocate of the Pan-African movement, with a longstanding interest in the global African diaspora, and served as the head of the sociology department from 1958 to 1961 at the University of Ghana.

Drake’s most important and influential works include Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945), a study on poverty, racial segregation and racism in Chicago, written in collaboration with African American sociologist Horace R. Cayton , Jr., and considered one of the best urban sociology jobs ever conducted in the United States; and Black People Here and There , in two volumes (1987, 1990), which collects a huge amount of research showing that prejudice against blacks began during the Hellenistic period in Greece, between 323 and 31 BC. .

Drake received the Dubois-Johnson-Frazier Award from the American Sociological Association in 1973 (now the Cox-Johnson-Frazier Award), and the Bronislaw Malinowski Award from the Society for Applied Anthropology in 1990. He died in Palo Alto, California in 1990, but his legacy lives on in a research center named after him at Roosevelt University and in the St. Clair Drake lectures held by Stanford. In addition, the New York Public Library houses a digital archive of his work.

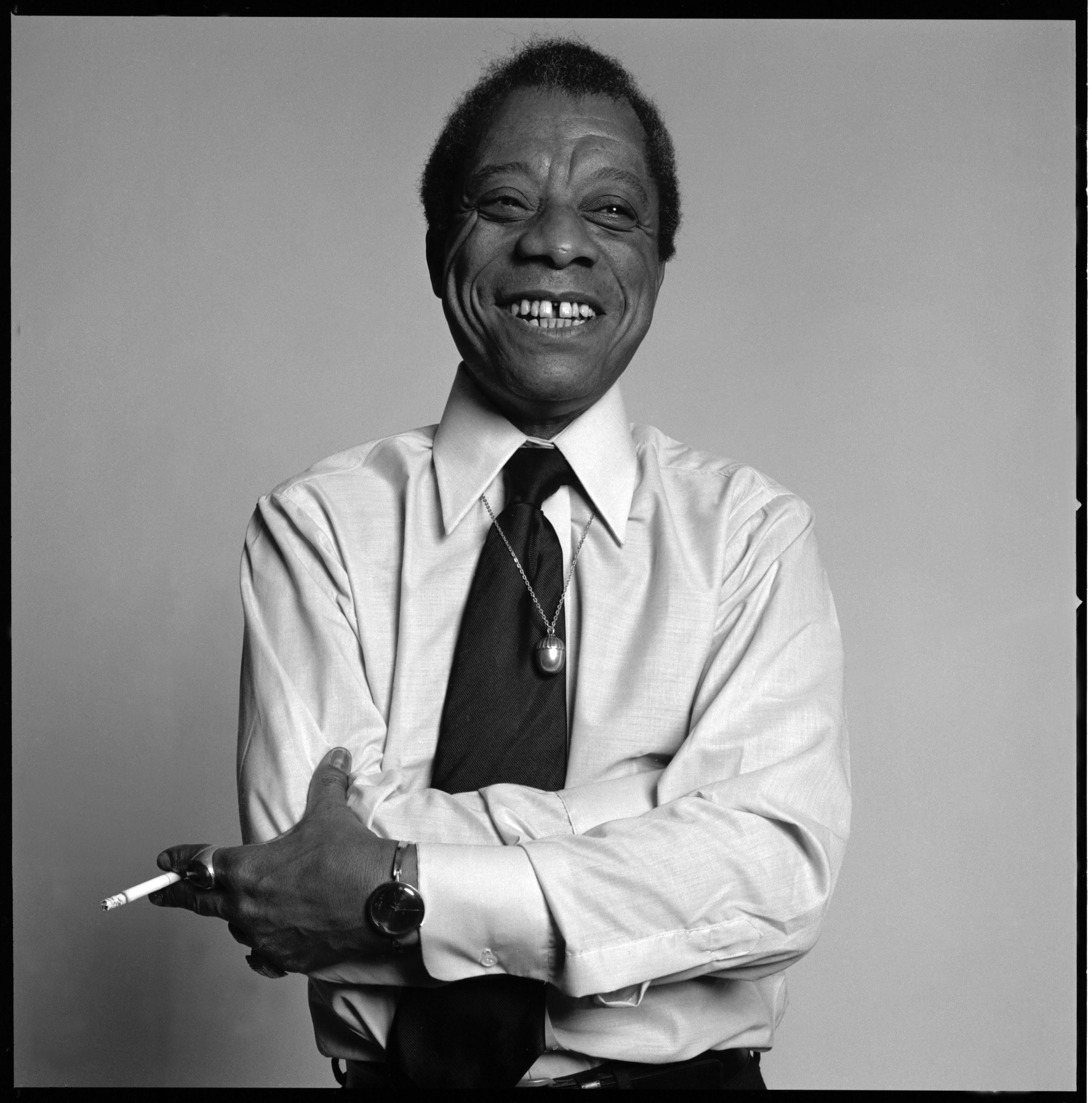

James Baldwin, 1924-1987

James Baldwin was a prolific American writer, social critic and anti-racism and civil rights activist. He was born in 1924 in Harlem, New York and grew up there, before moving to Paris, France, in 1948. Although he would return to the United States to speak out and fight for the civil rights of blacks as a leader of the movement, he spent il most of his adult life in Saint-Paul de Vence, in the Provence region of southern France, where he died in 1987.

Baldwin moved to France to escape the racist ideology and experiences that shaped his life in the United States, after which his writing career flourished. Baldwin understood the connection between capitalism and racism, and as such he was an advocate of socialism. He has written plays, essays, novels, poems and non-fiction books, all considered deeply valuable for their intellectual contributions to the theorization and critique of racism, sexuality and inequality. His most important works include Next Time the Fire (1963); No Name on the Street (1972); The Devil Finds Work (1976); and Notes of a native child.

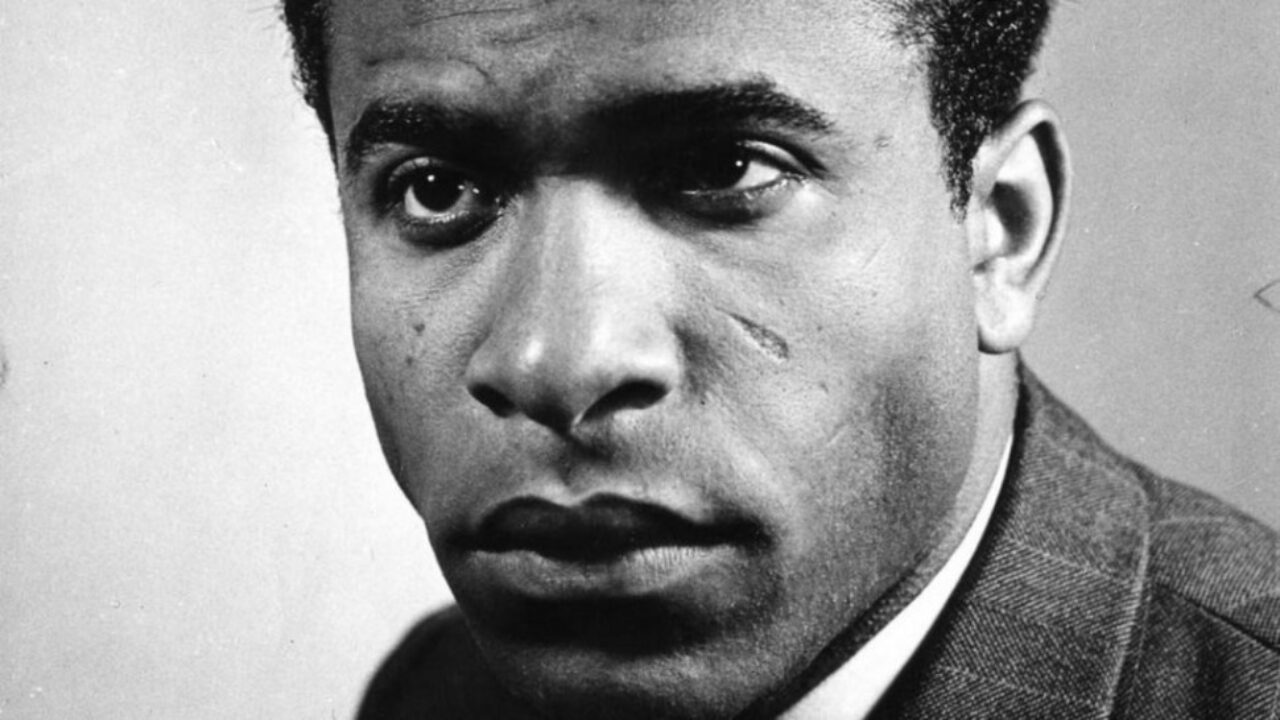

Frantz Fanon, 1925-1961

Frantz Omar Fanon, born in Martinique in 1925 (then a French colony), was a doctor and psychiatrist, as well as a philosopher, revolutionary and writer. His medical practice focused on the psychopathology of colonization and much of his social science relevant writings dealt with the consequences of decolonization around the world. Fanon’s work is considered profoundly important to postcolonial theory and studies, critical theory and contemporary Marxism. As an activist, Fanon was involved in the war for Algeria’s independence from France and his writings have served as inspiration for populist and postcolonial movements around the world. As a student in Martinique, Fanon studied with the writer Aimé Césaire. He left Martinique during World War II as it was occupied by the oppressive French naval forces of Vichy and joined the Free French forces in Dominica, after which he traveled to Europe and fought with Allied forces. He returned briefly to Martinique after the war and earned a degree, but then returned to France to study medicine, psychiatry and philosophy.

Fanon’s first book, Black Skin, White Masks (1952), was published while living in France after earning his medical degree, and is considered an important work for the way it processes the psychological damage done to blacks by colonization. , including how colonization instills feelings of inadequacy and dependence. His most famous book The Miserables of the Earth(1961), dictated while he was dying of leukemia, is a controversial treatise in which he argues that, because they are not seen by the oppressor as human beings, colonized people are not limited by the rules that apply to humanity, and therefore have the right to use violence while fighting for independence. Although some read him as an advocate of violence, it is actually more accurate to describe this work as a critique of the tactics of non-violence. Fanon died in 1961 in Bethesda, Maryland.

Audre Lorde, 1934–1992

Audre Lorde, was born in New York City to Caribbean immigrants in 1934. She is a noted feminist, poet, and civil rights activist. Lorde attended Hunter College High School and completed her undergraduate degree in 1959, and subsequently a Master of Library Science from Columbia University. Later, Lorde became a resident writer at Tougaloo College in Mississippi and, subsequently, was an activist for the Afro-German movement in Berlin from 1984 to 1992.

During her adult life Lorde married Edward Rollins, birth two children, but later divorced and embraced her lesbian sexuality. Her experiences as a black lesbian mother were central to her writing and fueled her theoretical discussions of the intersecting nature of race, class, gender, sexuality, and motherhood. Lorde used her experiences and perspective to elaborate important critiques of the whiteness, nature of the middle class and the heteronormativity of feminism in the mid-twentieth century. He theorized that these aspects of feminism actually served to secure the oppression of black women in the United States, and expressed this view in a speech often given at a conference entitled “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

All of Lorde’s work is considered of value to social theory in general, but her most important works in this regard include Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power (1981), in which she frames the erotic as a power of source. , joy and emotion for women, once it is no longer suppressed by the dominant ideology of society; and Sister Strangers: Essays and Discourses (1984), a collection of works on the many forms of oppression Lorde experienced in her life and the importance of embracing and learning from difference at the community level. Her book, The Cancer Journals, which chronicled her battle with disease and the intersection of disease and black womanhood, won the 1981 Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award.

Lorde was the New York State Graduate Poet from 1991 to 1992; received the Bill Whitehead Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992; and in 2001, Publishing Triangle created the Audre Lorde Award in honor of lesbian poetry. He died in 1992 in St. Croix.