Thursday February 2, 1968, in Toulon. Rescue operations for the submarine La Minerve are suspended. Five days after the submersible disappeared, hope of finding survivors has vanished. “From the start of the rescue operation, we didn’t really believe in it anyway,” recalls Georges Kévorkian. At the time, this young engineer from the Directorate of Naval Construction was tasked with leading the rescue operations from Monday, January 29, two days after the last recorded communication with the submarine.

More than half a century later, Monday July 22, 2019, the submarine was found . The search for his wreck resumed Thursday, July 4 off Toulon by more than 2,000 meters deep, with advanced technological means. An Ifremer underwater research drone, capable of covering 10 km2 per day in a research area which has several hundred, had been launched, in connection with a surface oceanographic vessel, which analyzed the data reported each evening.

Will this discovery unravel the mystery surrounding the drama? How did the submarine sink? Damaged? Human errors? Technical problems ? A conjunction of the three ?. The army, which has never lifted the gray areas that surround it, will be able to give answers to families who were beginning to despair.

AT 7:55 AM, “LA MINERVE” PLUNGES INTO SILENCE

EAt the start of 1968, the waters of the Mediterranean were rough. The mistral blows at 100 km / h. It is under these conditions that La Minerve is preparing to carry out an exercise with an airplane. “The first to see the other has won” , explains Georges Kévorkian. The submarine dives as the Bréguet Atlantic, which took off a few minutes earlier from the naval air base of Nîmes-Garons, arrives in the area at 7.15 am. A first contact between the two devices is made four minutes later. But climatic conditions make communications difficult. At 7.45 am, the plane announces that it is giving up its last radar check, says Liberation . Ten minutes later, response from La Minerve by the voice of the second master Nicolas Migliaccio, in charge of the radio links:

I understand that you are canceling this check. Did you hear me?

This will be the last sign of the submarine’s life.

The following ? Mystery. On land and in the plane, due to the weather, we don’t really worry about this silence. La Minerve must return to port no later than Sunday, January 28, at 1 a.m. At the fateful hour, still nothing. Georges Kévorkian recounts the scene in his book, Accidents de submarine français 1945-1983 (ed. Marines): “Chief, I saw matafs [sailors] this morning … who told me that La Minerve was lost: it did not return to the base as planned ” , reports a worker.

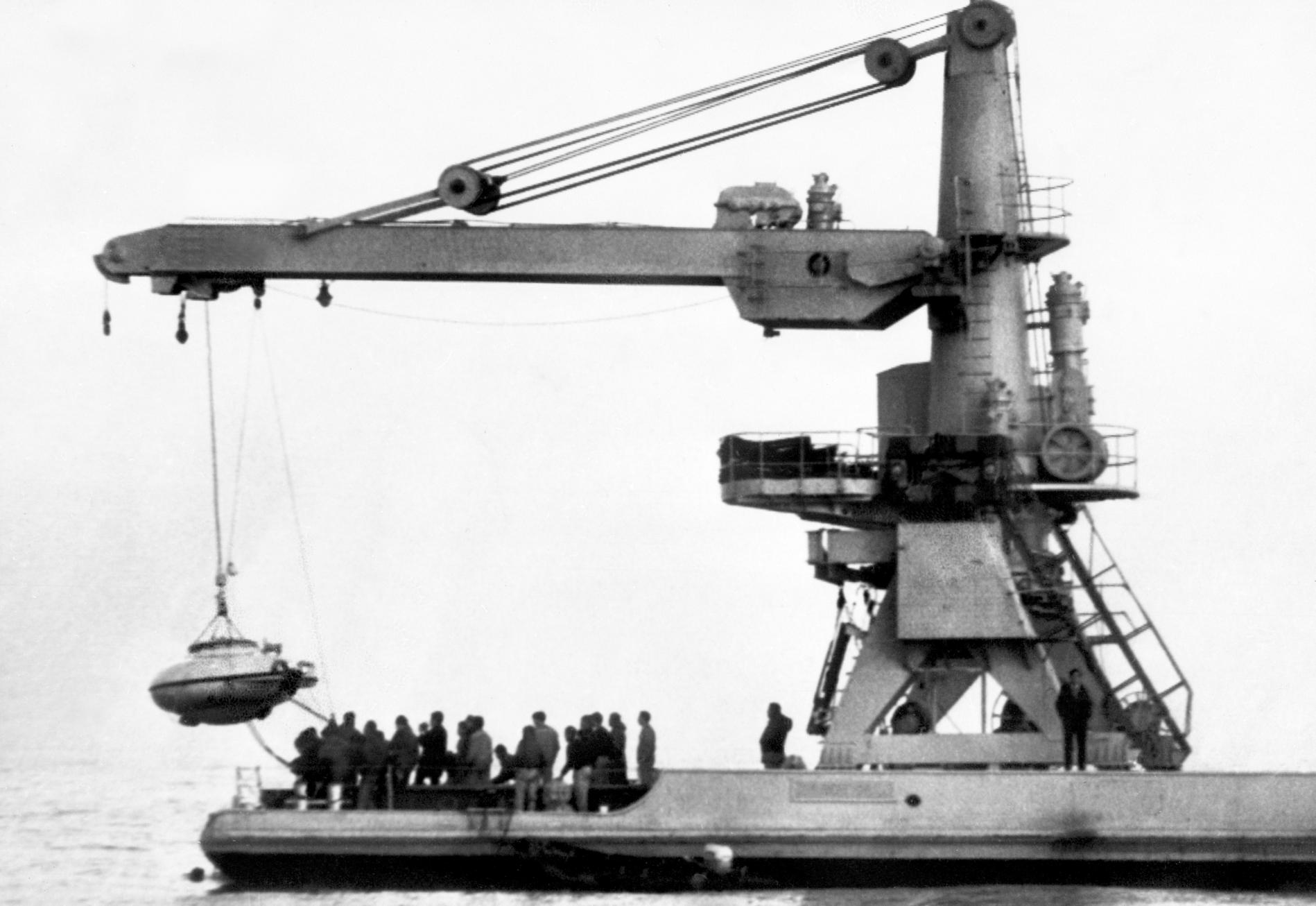

The research officially started at 2:15 a.m. That is 18 hours and 25 minutes after the last communication from the submarine. La Minerve has around a hundred hours of oxygen, time is running out. The equipment at the time did not allow to probe the seabed very deeply. However, off Toulon, they can reach 2,000 m. It is precisely in this sector, south of Cape Sicié, that La Minerve carried out its exercise. Despite the twenty boats that came to help with the research, helicopters, planes and even Commander Cousteau’s diving saucer, the submersible remains nowhere to be found.

‘La Minerve’ probably sank 1,000 m deep. The only visible trace of the sinking was an oil stain on the surface.

The Armed Forces Information and Public Relations Service (Sirpa)

Present on the aircraft carrier Clémenceau mobilized for research, Joël Lannuzel, 30 years old at the time of the tragedy, says he “made tours and tours in the Mediterranean” . “Oil a single spot of course we never talk” , he argues. Second radio master on La Minerve from March 1962 to October 1965, he knew the building “like his pocket” . For him, only a “collision with another ship” could sink La Minerve . One hypothesis among others.

A TRUTH THAT NEVER EMERGES

VSow could this 800 ton monster disappear without leaving the slightest trace? The vagueness remains half a century later. “For eight, ten days, we said anything and everything , remembers Thérèse Scheirmann-Descamps, widow of second master Jules Descamps. I was even asked not to read the newspapers.” We can see the blossoming of far-fetched theories like a Russian coup de force. Others are more plausible.

The most common ? A “snorkel” problem. It is in fact two tubes, one supplies air to the submarine, the other allows to reject the exhaust gases. When the building is in periscope immersion, that is to say a few meters from the surface, these pipes come out and water can enter them. Normally, a valve closes to prevent flooding. This January 27, 1968, an incident could have prevented this valve from functioning properly, La Minerve then filled and sank irreparably.

This Daphne-type submarine could dive up to 525 m. Beyond that, the hull cannot withstand the pressure. By sinking in this area off Toulon, La Minerve sank much lower and must have imploded. In his book, Georges Kévorkian mentions a “signal likely to result from the brutal crushing at a depth of 700 m of a ‘container’ containing about 600 m3 of air at atmospheric pressure” . A description that could correspond to the missing submarine. This signal was recorded by various seismological stations “at 7 hours 59 minutes and 23 seconds, to within a few seconds” . That is four minutes after the last communication from La Minerve .

This theory of the snorkel is however rejected by the writer since “a few minutes before its disappearance, it is not proven that the submarine was sailing with a snorkel” . The collision thesis, defended by Joël Lannuzel, was also considered. The area was used extensively by commercial vessels. But again, this was only one possibility among many.

Of course, we thought of a collision. But against what? Was a boat or any object found?

The Sirpa

There remains human error, which everyone refutes. All eyes turned to Commander André Fauve. Could he have initiated a too perilous maneuver, as Georges Kévorkian implies? Admiral Thierry d’Arbonneau, a young officer at the time of the accident, was one of Captain Fauve’s students. His description of a “hyper-competent” man makes this hypothesis unlikely. “He was our maneuver officer, he taught us to navigate. He had an obvious aura, he was young, calm, level-headed ” , explains the admiral. However, despite a “respected and recognized” captain , a trained crew and a vessel in good condition , La Minerve never ascended.

THE IMPOSSIBLE MOURNING OF FAMILIES

En sinking off Toulon, La Minerve left behind 52 bereaved families, 28 orphans and 17 widows. Martine Coustal is one of them. She was 18 at the time and was to marry Marcel Coustal, an electro-mechanic on board, a few days after the return of the submarine. Fifty years later, this woman with a singing accent from the south of France has not forgotten anything. “We always think about it, ” she breathes, ” but the most moving thing is to be at the place of the commemoration.”

On January 28, 1968, when she received a visit from her stepfather, she thought of once again approaching her next marriage. She is far from imagining the worst. She understands that day that her husband will never come back. The baby she is expecting will be an orphan. The boy will be born two months later and will be called Marcel. In tribute. She will marry posthumously on July 10, 1968 and will obtain the right to bear the name of Coustal. “The marriage was very, very difficult,” she admits. But despite the loss and the pain, Martine was never revenge.

He had chosen this life, I am for them to be left alone. Nothing will bring them back to us. You need to go forward.

Martine Coustal

Thérèse Scheirmann-Descamps, the widow of the second master Jules Descamps, she does not want to inflict new suffering on herself either. But, she hopes for answers. “We have been expecting it for fifty years , ” she says . 25 years old at the time of the tragedy, she also remembers: “On January 28, 1968, I was baking a cake for my husband whose birthday was. At 10 o’clock, I heard the sirens. At noon, we told me he would be late … I immediately understood that he would never come home. ” The following days are terrible. “I was calculating the number of hours he could live, while taking care of my children” , she slips. She also cannot help but imagine the suffering of the last moments lived on board by her husband and her companions.

For Thérèse, as for Martine, life takes over. Sometimes brutally. Their children grow up without their fathers. Absence is a heavy burden to bear. “There was great suffering, my daughter, who was going to be 3 years old when her dad died, had trouble building herself. My son also had great problems. ‘psychological support at the time ” , testifies Thèrèse Scheirmann-Descamps. For the two women, out of the question to miss the commemorations of the 50th anniversary, although it is “very painful” .

Jean-Paul Krintz, he will miss the call in Toulon. This former assistant manager on board La Minerve died a few months ago. He should have been on board the submersible on January 27, 1968. But, young married and at the end of his contract, he had been exempted from practicing. Gnawed by guilt, “he has always had a hard time forgetting all that,” admits Patrick Meulet, president of the “ruby” section of the General Association of Submariners (AGASM). In 2010, the former submariner said his discomfort in La Dépêche du Midi :

For forty years, I have remained closed. I didn’t feel out of place.

Jean-Paul Krintz

Perhaps he thought he should be with them, at the bottom of the Mediterranean, with his companions. This place that has never really been identified and that works so hard for families. “When you lose someone, you want to know where they rest,” insists Thérèse Scheirmann-Descamps.

THE “GRANDE MUETTE” IS SILENT

VSworryingly years later, with improved techniques, new research could have been done, but nothing was ever done. “We could have relaunched them , protests Patrick Meulet. To say that we cannot find him is shocking, especially since we know the sector where he is supposed to be.” The president of AGASM joined the navy one year, to the day, after the drama of La Minerve and supports the families’ desire for truth. How? ‘Or’ What ? Why ? Where ? These are the questions that resonate in people’s minds. “Why such silence?” asks Thérèse Scheirmann-Descamps. Are things hidden? “How do you explain an accident when we have never found anything? ” Defended the Information and Public Relations Service of the armed forces in 2000.

The authorities could not decently repeat ‘we don’t know anything’ forever. What would it have served? But they didn’t try to hide anything.

Eighteen years later, the rhetoric has not changed. Captain Bertrand Dumoulin, spokesperson for the French Navy, confirms that “the causes of the accident have never been elucidated” .

“The Eurydice was indeed found when we went down to 1000 m” , contests Patrick Meulet. He knows what he is talking about. Patrick Meulet was on board the submersible, another Daphne-type submarine, three months before its sinking on March 4, 1970. Before sinking in the Mediterranean, the Eurydice had also served for the national homage paid to the crew of La Minerve by General De Gaulle, February 8, 1968.

By embarking on board for a dive, despite its size – 1m96 – and its overweight, the President of the Republic had greeted these “volunteers who had accepted the sacrifice in advance and who had made a pact with danger” . “The general liked the strength of the symbol , recalls Admiral Thierry d’Arbonneau. He wanted to prove that the nation was united in this tragedy and to show the confidence he had in the submarines and their crews.” This “pact with danger” , recalled by De Gaulle, is one of the reasons why no legal action has been taken by the families: “Never in our life, we would have done that!” Says Thérèse Scheirmann -Some camps. Out of respect for the function and commitment of submariners. ”

The Eurydice and La Minerve , two “Daphne”, were the prestige of the French navy – and there could have been a third drama but the Flore avoided the sinking on February 19, 1971 (the snorkel had been clearly implicated and improvements were made in the wake to avoid new accidents). Between 1965 and 1975, around ten Daphne-type submersibles were sold to South Africa, Pakistan and Spain. Did economic interests dictate the army’s silence? “Clearly, no! Replied Bertrand Dumoulin. If the cause of the accident were known, it would have been absurd not to communicate it to our foreign partners.”

“I blame the staff. They were able to hide something, we do not know why” , does not budge Patrick Meulet. He, like the families of the missing, cling to this fiftieth anniversary of the tragedy. After this date, the secrecy surrounding La Minerve should be lifted. Thérèse Scheirmann-Descamps is impatiently awaiting this.

Twenty years after the tragedy, we were told to wait. At thirty and forty too. There are limits, it’s starting to do well.

She hopes. For her. For his children. Without really believing it. Patrick Meulet, either, is not convinced that all the light will be shed on the drama. Because the army could very well keep silent about possible answers. And justify once again its nickname “Grande Muette”. Patrick Meulet sighs: “We hope that after fifty years, we will succeed in making her speak.”